This hereby ends the postseason blog entry blackout for The Orioles Warehouse. Sorry for not being explicit about the hiatus, but it was not planned beforehand; it just unfolded that way because nothing really significant happened to the Orioles for three weeks after the end of the regular season, and so no commentary was warranted. But now baseball's offseason has begun, and so resumes our study of the anthropic version of Icterus galbula (translation: the Baltimore Orioles).

The red October surprise

But first, a few words on the thrilling postseason. The unquestionable highlight, in terms of sheer drama, was the Red Sox coming back against all odds in the ALCS to snatch the pennant from the Yankees' grasp. The unprecedented, storybook fashion in which the Yankees lost made it all the more satisfying to Oriole fans, whose hate for the Red Sox is exceeded only by their enmity for the Yankees. (If you totally missed the ALCS, here's a drive-by recap: the Yanks held the Sox at bay in Games 1 and 2 and blasted them to smithereens in Game 3 to take a seemingly invincible 3-0 lead in the series; but in Games 4 and 5, Boston eked out two extra-inning nail-biters in sudden death, then Curt Schilling and his patched ankle triumphed in Game 6, and in Game 7 long-locked Johnny Damon knocked two longballs to send the Sox to victory.)

It's tough for the Oriole community to have to watch a postseason with their favorite team on the sidelines. But from the perspective of a fan of the game of baseball, this one turned out well when the Red Sox shattered the Curse of the Bambino by sweeping the Cardinals in the World Series. It would have been nice if the Cards had been more competitive and stretched the series to six or seven games. But for once, Boston had everything go their way in the end. Ex-Oriole prez Larry Lucchino, now president and CEO of the Red Sox, is finally enjoying his just deserts. And native New Englanders across the country, a healthy portion of whom reside in the Baltimore-Washington region, are floating in the euphoria of their team's victory. Of course, they will henceforth have to shed their tiresome woe-is-me attitudes and assume the unfamiliar mantle of frontrunners from the Yankees. But let the Red Sox and their fans have their day in the sun. If anyone deserves it, they do.

Epstein leads with his head

The postseason confirmed that Red Sox general manager Theo Epstein is one of the game's sharpest decision-makers. Following last year's Grady Little/Pedro Martínez debacle, Epstein hired a field manager, Terry Francona, who handled the club like the seasoned professional that he is and made no dubious moves in the postseason (except perhaps his insertion of Pedro for a trivial relief inning in Game 7 of the ALCS). And although he could have stood pat after reaching the seventh game of the ALCS in 2003, Epstein identified his team's key weaknesses (lack of high-end pitching, suspect infield defense, and lack of team speed) and addressed them in the offseason and regular season by acquiring Schilling, Keith Foulke, Doug Mientkiewicz, Pokey Reese, Orlando Cabrera, and Dave Roberts. Of course, it helped enormously that his team had the second-highest payroll in the league ($125 million on Opening Day, far behind the Yanks' $183M but well ahead of third-place Anaheim's $101M), giving him the flexibility to acquire nearly anyone he wanted. And Boston's medical staff deserves a special award for their ad hoc repair of Schilling's ankle tendon for his final two starts of the postseason. But none of Epstein's big acquisitions backfired, and that includes his gutsy trade of his injury-impaired shortstop, Nomar Garciaparra, for Cabrera and Mientkiewicz. The final product was a well-rounded, championship-caliber team that had every right to win it all, and it did.

For those who care about Oriole-related matters: Epstein got started in baseball as a public relations intern for the Orioles in 1992-1994. He then followed Lucchino to the San Diego Padres, where he rose to director of baseball operations while he earned a law degree at UCSD. In 2002 he migrated with Lucchino to Boston and subsequently became the game's youngest GM at age 28. If Peter Angelos had been able to retain Lucchino as president of the Orioles upon buying the team in 1993, could there have been a 2004 Orioles team with Epstein at the helm? Perhaps, although Epstein, who grew up in Brookline, Mass., has been a Red Sox fan since childhood and would have jumped at the chance to be their GM if the position became available.

Baseball's mind game steps forward

The success of the Red Sox should give another boost to the sabermetric community. In addition to Epstein, a sabermetrically aware GM, at least two other people of a sabermetric bent are part of the championship team's brain trust: longtime baseball analyst and writer Bill James, now Boston's senior baseball operations advisor; and Voros McCracken, famed for his defense-independent pitching analysis and a consultant for the organization since late 2002. If the Moneyball-documented success of the Oakland Athletics catalyzed a sabermetric movement in baseball, the recent éclat of the Red Sox should only increase the prevalence of statistically knowledgeable analysts and GM's in front offices around the league.

It's clear that the management and analysis of information is more important today than it ever has been to the sport (or to business in general—but that's another story). Technology has made it possible not only to access and store reams of performance-related data on players, but also to quantitatively measure and optimize aspects of player performance—think defense and pitching—that have long been riddled with guesstimation and uncertainty. The problem is knowing what to do with all that information, and that is why it is critical to have smart, analytical people in every area of an organization, including the front office, the scouting department, the coaches, and the field manager.

The Oriole angle

Will the Orioles be at the forefront of this activity, pouring money and manpower into information technology, quantitative analysis, and research and development? Or will they be content to rely on tried and tested (and arguably outdated and inefficient) methods in running their organization? Most of the evidence so far suggests the latter rather than the former, although it's hard to be certain because club executives have been tight-lipped about their internal evaluation processes. A recent reflection by former Orioles intern Josh Goodstein in the Yale Herald paints a dim view of the Orioles' management, at least on the non-baseball side.

However, the franchise has a chance to make a major step in the direction of data-driven decision-making when it chooses its next director(s) of scouting and player development. (News reports have indicated that the O's may hire one person to handle the former duties of Tony DeMacio and Doc Rodgers.) More on that in an upcoming article.

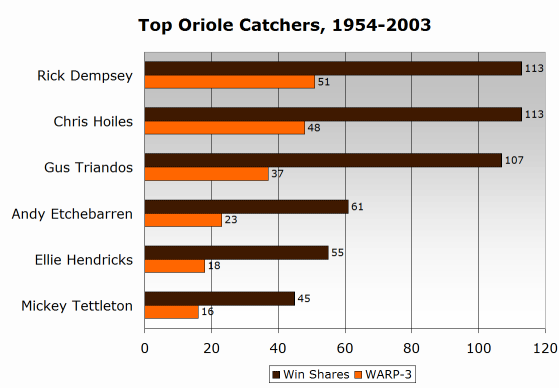

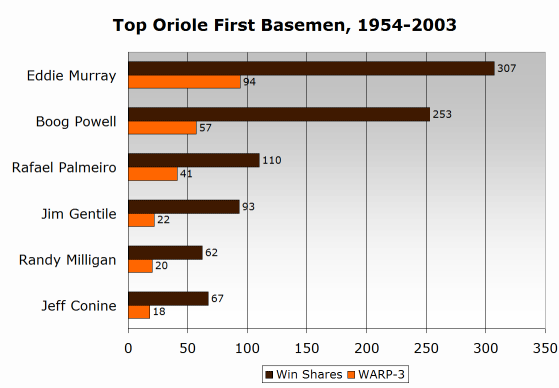

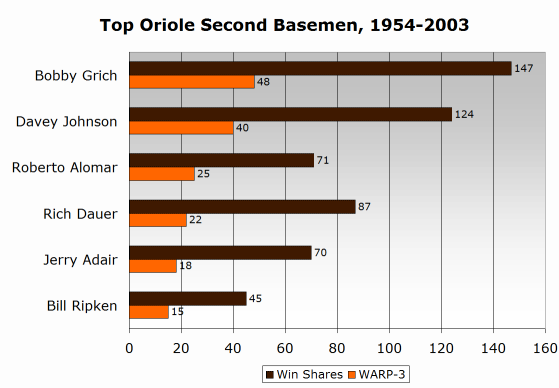

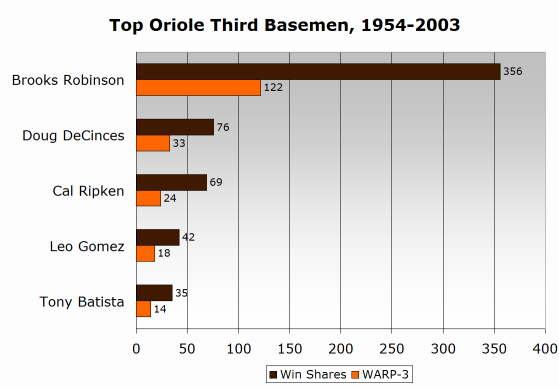

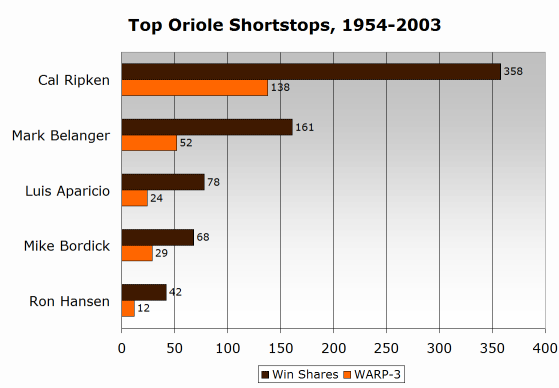

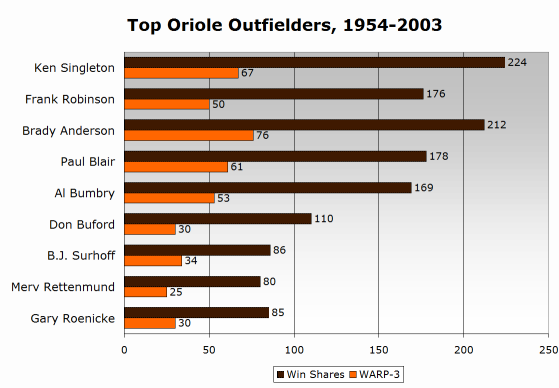

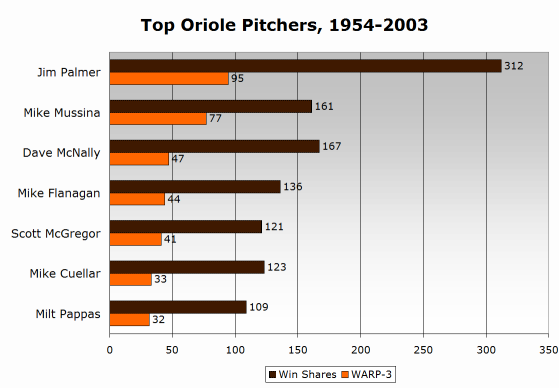

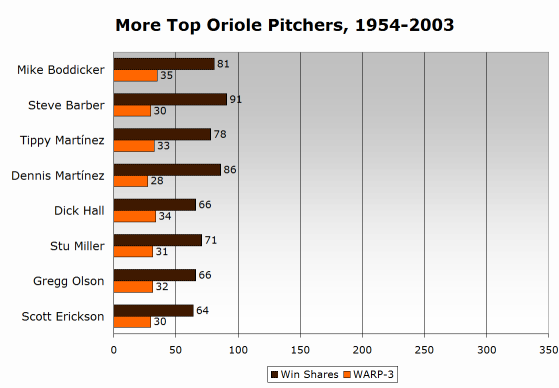

Other topics that will be covered soon: the re-signing of Rafael Palmeiro and other recent roster news; the D.C. baseball saga and its effect on the Orioles; a review of the Birds' 2004 season; a look at the Orioles' offseason needs; more perspectives on Miguel Tejada; and the continuation of the historical Orioles series (yes, really this time).