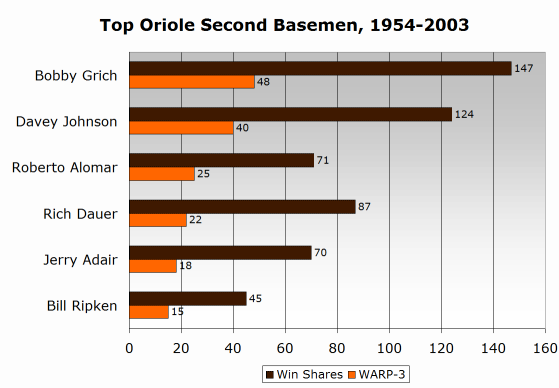

Top three second basemen in modern Orioles history:

- Bobby Grich (1970-1976)

- Davey Johnson (1965-1972)

- Roberto Alomar (1996-1998)

The competition for the top all-time Oriole second baseman was more heated than the battles at other positions. No second sacker in modern club history has combined performance and longevity the way that Brooks Robinson did at third base or Cal Ripken did at shortstop. Baltimore has had several noteworthy second basemen, including a couple whose overall careers are worthy of Cooperstown. But because none of them stayed in town longer than a decade, none was able to compile the kind of counting stats that would make him the indisputable king at the position.

Grich: pithy rich

But there was one second baseman who combined great offense and defense for long enough to separate himself from the pack, and that was Bobby Grich. Taken in the first round of the 1967 amateur draft, Grich was the first Oriole draftee to become a star at the big-league level. But before that, he had to persevere in the minors a little longer than necessary because there was just no unseating Baltimore's airtight middle infield of Mark Belanger and Davey Johnson.

In 1971, Grich forced the Orioles to take notice with a phenomenal performance at Rochester, the organization's top minor-league affiliate. His league-leading .336 batting average, 124 runs scored, and 32 home runs compelled The Sporting News to name him their Minor League Player of the Year. In 1972, Grich began to get playing time at shortstop for the Birds in lieu of the light-hitting Belanger and was even selected to the All-Star team at that position. But a permanent job did not develop for him until Johnson was traded to Atlanta in November, leaving the keystone corner to Grich.

Grich seized the opportunity and thrived. He became a superior defender at second, winning Gold Gloves there from 1973 to 1976. Grich was a dangerous hitter for the Birds as well. Although his power would not fully develop until after he left Baltimore, his on-base percentages cracked the league's top ten every year from 1973 to 1976. Grich's hitting is underrated by many people because a large proportion of his offensive value came from his prodigious walk totals. Beginning in his second full season of 1973, he drew 107, 90, 107, and 86 free passes, each time finishing among the league's top five walkers. Those walks, along with a knack for getting hit by wayward pitches (his 20 HBP in 1974 rank as the third-highest single-season total in club history), helped Grich post high on-base percentages despite pedestrian batting averages (he finished with a .266 career average, .262 for Baltimore).

Grich compiled a 125 lifetime adjusted OPS+ and a .295 era-adjusted Equivalent Average in his seventeen seasons with the Orioles and the Angels; his .297 EqA as an Oriole places him 11th in club history among batters with at least 2000 PA. Needless to say, those are extremely impressive figures for a second baseman.

Overall, Grich's Baltimore batting line was .262/.372/.405. That .372 on-base percentage is the eighth highest for a batter in the modern Oriole era (minimum 2000 PA). Grich's 32 Win Shares in 1974 are the highest single-season total ever by an Oriole second baseman and are tied for the tenth best season among all Birds. His career totals of 147 Win Shares and 48 WARP-3 top all second basemen in Oriole history since 1954. And he accomplished all of that in just five full seasons in Baltimore. After the 1976 season Grich became one of the first Orioles to leave the team under the newly formed system of free agency, and he spent the rest of his career starring for California Angels.

Others have made the case that Grich should be in baseball's Hall of Fame, and there will be no pointed dissent from that view here. Grich has never received much attention for the Hall because he was a jack of all trades who lacked eye-popping numbers in any one statistical category. His relatively low totals in hits (1,833) and home runs (224) should not disqualify him from consideration, in part because he drew so many walks but largely because he played second base, one of the most demanding positions defensively, and played it well. Second basemen are underrepresented in the Hall, so the traditional offensive benchmarks (e.g., 3,000 hits, 500 home runs) need to be lowered somewhat for keystone minders. Ryne Sandberg (346 career Win Shares) and Lou Whitaker (351 WS) may be at the front of the line for the Hall among second basemen, but not far behind them is Grich (329 WS). And if Bill Mazeroski (elected by the Veterans Committee in 2001 despite just 219 WS) belongs in the Hall, it's hard to argue that Grich does not. Although Grich has no World Series-winning homers to his credit, he was a far more accomplished hitter than Mazeroski and just slightly worse as a fielder (he had 5.64 WS/1000 inn. compared to Maz's 6.18). Grich should eventually receive baseball's highest honor if the voters are just.

Johnson: knew how to win, but eventually wore thin

Grich's predecessor, Johnson, was no slacker of a second sacker either. Although his extraordinary success as a manager in the '80s and '90s would overshadow his achievements as a player, Johnson was a more than competent second baseman in the late '60s and early '70s, making major contributions to four pennant-winning Oriole clubs. He broke into the majors with Baltimore in 1965, was the regular second baseman on the '66 championship squad, and became proficient enough at bat and in the field to be named an All-Star from 1968 to 1970.

As a hitter, Johnson had a decent eye at the plate and gap power, hitting .259/.330/.378 with the O's. His best year with the bat as an Oriole was 1971, when he hit .282/.351/.443 with career highs of 18 home runs and 72 RBI. After an off year in 1972, he was traded to Atlanta and immediately made the Orioles look stupid by hitting 43 homers the following year for the Braves. The 42 homers he hit as a second baseman that year remain a league record for the position. The power spike proved to be transient, though, as Johnson returned to a more usual 15 homers in 1974 before taking a two-year detour to play for the Yomiuri Giants of Japan, then returning to the States to close out his career with the Phillies and the Cubs. Overall, Johnson's offense was a few ticks below that of Grich, but he had an adjusted OPS+ greater than 100 (i.e., better than a league-average hitter) in five out of the seven full seasons he played in a Baltimore uniform. His era-adjusted Oriole EqA was .268.

Johnson could play the field, too; he fetched the American League's Gold Glove award at second base from 1969 to 1971, meaning that he and Grich combined for seven of the eight AL Gold Gloves at second between 1969 and 1976. Their dynasty was broken only by Boston's Doug Griffin in 1972. It is interesting, though, that neither Grich nor Johnson won a Gold Glove after leaving Baltimore.

While Johnson's first act with the O's was successful, so was his return engagement as manager. But it was fraught with controversy and ended abruptly. Johnson returned to the Orioles in 1996 to nudge a contending club to the next level, and he did just that, winning the AL wild card in '96 and a division title in '97 and taking the team to the league championship series each year. But a rocky relationship between Johnson and owner Peter Angelos ended with Johnson resigning after the 1997 season, mere hours before he was named the AL's Manager of the Year. Johnson was one of baseball's finest managers over the last two decades, compiling a record of 1,148-888 for a .563 winning percentage for the Mets, Reds, Orioles, and Dodgers.

Johnson's managerial contributions give him some extra credit in this analysis, but they are not enough to push him ahead of Grich on the list of the Orioles' top second basemen. Grich was simply better than Johnson in every aspect of the game as a player; he compiled more Win Shares than Johnson did despite playing about two fewer seasons for Baltimore.

Alomar: a hit, but roasted on the spit

One of Johnson's charges in 1996 and 1997, Roberto Alomar, was no stranger to controversy, either. Alomar's spitting on umpire John Hirschbeck during an argument in September of '96 resulted in a five-game suspension to begin the 1997 season. Then his truancy for two team functions in the summer of '97 prompted Johnson to fine him $10,500. The Birds' manager had the misjudgment to ask Alomar to write the check for the fine to a charity operated by Johnson's wife. This decision, made without the consent of the team, widened the rift between Johnson and Angelos that ultimately led to Johnson's resignation.

But when Alomar was with the Orioles, he was also making plenty of headlines for his on-field heroics. After coming to the team as a free agent in the 1995-96 offseason, Alomar formed a formidable keystone combo with first Cal Ripken and then Mike Bordick, winning Gold Gloves in 1996 and 1998 (in 1997 he missed 50 games due to injury and suspension) and being named to the All-Star team each year from 1996 to 1998.

At the plate, Alomar was one of the most well-rounded hitters in the game, batting .312/.382/.480 in his three years with the Birds. Although he did not accumulate the plate appearances required to ascend the club's all-time leaderboard, he does own a club record with his 132 runs scored in 1996. That year, his first and best with the O's, Alomar hit .328/.411/.527 with 43 doubles, 22 home runs, and 94 RBI and earned 31 Win Shares. His game-winning home run in the deciding game of the 1996 ALDS against Cleveland is one of the most memorable postseason moments in team history.

During Alomar's Oriole tenure he averaged an impressive 28 Win Shares per 162 games, second only to Grich's 30 WS/162 among Oriole second basemen, and compiled a .305 era-adjusted EqA. Unfortunately, Alomar's tenure with the team ended unhappily, as he had a down year (by his high standards) in 1998 and left as a free agent after the season. But Alomar's performance during his stint with the Orioles and throughout his itinerant career has been unquestionably stellar and makes him a lock for Cooperstown, assuming he doesn't spit on or otherwise irritate any baseball writers between now and the time he becomes eligible.

Honorable mentions

Other Oriole second basemen of distinction are Rich Dauer (1976-1985), Jerry Adair (1957-1966), and Bill Ripken (aka Billy) (1987-1992, 1996).

Dauer has the distinction of holding down the starting second baseman's job for longer than any other Oriole. He owns the club record with 964 games played at second base, just beating out Johnson's 947. Dauer also played 242 games at third base. Drafted by Baltimore in the first round in 1974, Dauer was a sound player, though not a spectacular one, during his career, all of which was spent with the Orioles. Dauer hit .257/.310/.343 lifetime for an 83 adjusted OPS+ and a .247 EqA. Although he did not have much power or on-base ability compared to the man he succeeded, Grich, Dauer was ridiculously difficult to strike out; he whiffed in just 5.2% of his plate appearances as an Oriole, the lowest frequency in club history among players with at least 2000 PA. Dauer also had a reliable glove, making just one error in 87 games at second base during the 1978 season. That year he handled 86 consecutive games and 425 chances without a miscue as a second baseman, both single-season records at the time (Ryne Sandberg eclipsed those marks in 1989). Dauer's lifetime fielding percentage at second base was an outstanding .987, although his range was not quite as good as his predecessors'.

Adair was the Orioles' second baseman in the '60s before Johnson took over. A stellar defender and a hitter with some pop, he averaged .258/.297/.366 at the plate during his Oriole career, which began in 1958 and ended with a trade to the White Sox in early 1966. Adair never won a Gold Glove, but he certainly could have and probably should have; he led the league in defensive Win Shares by a second baseman in 1964 and 1965, and his 89 consecutive games and 458 consecutive chances without an error from July 22, 1964, to May 6, 1965, were major-league records. (The distinction between Adair's record and Dauer's is that Dauer's streak occurred entirely within the same season, while Adair's spanned multiple years.)

Bill Ripken was another defensively reliable but offensively slight second baseman. He had two good years at the plate: his rookie half-season in 1987, when he hit .308/.363/.372, and his 1990 campaign, when he hit .291/.342/.387. But otherwise he was a feeble hitter, as he averaged .243/.292/.313 as an Oriole. His glove was better, as he teamed with brother Cal to give the Birds one of the league's better double-play combos. Though not blessed with great range, Bill's fielding percentage of .9865 as an Oriole second baseman is second only to Dauer's .9874 (minimum 300 games). Win Shares and Clay Davenport's fielding translations rate the younger Ripken as slightly above the league average as a defender.

Next: third basemen.