Top three catchers in modern Orioles history:

- Rick Dempsey (1976-1986, 1992)

- Chris Hoiles (1989-1998)

- Gus Triandos (1955-1962)

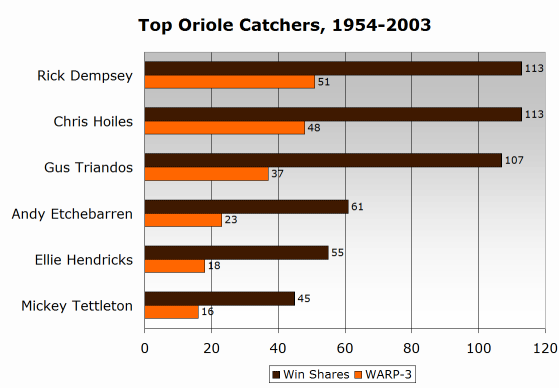

The battle for the top Oriole catcher is between two players with contrasting skill sets: Rick Dempsey, a defensive wizard with a mediocre bat, and Chris Hoiles, an offensive force with a mediocre throwing arm. The two virtually tied for the most career Win Shares among Oriole catchers with 113. Dempsey finished with a small advantage in WARP-3, 51 to 48.

The paths they took to reach those totals could hardly have been more different. Dempsey earned roughly half of his Win Shares as a fielder and half as a hitter; Hoiles earned about 70% of his Win Shares with the bat. Dempsey threw out 40% of opposing basestealers in an era when the steal was a significant component of offense, but his regular-season hitting numbers for Baltimore were feeble at .238/.319/.355 (BA/OBP/SLG). Hoiles threw out just 29% of opposing baserunners but swung the stick better than some first basemen, hitting .262/.366/.467 for his career. His 1993 season (.310/.416/.585, 29 HR, 80 RBI) is one of the best offensive years in history by a catcher not named Mike Piazza.

A host of other factors, however, push Dempsey over the top. One is the strength of his overall playing career: Dempsey saw action in 1,766 games over 24 seasons in the majors stretching from 1969 to 1992. He earned a total of 158 Win Shares and 64 WARP-3 for six different teams. Hoiles's ten-year big-league career, on the other hand, began and ended with the Birds, as an accumulation of aches and pains eventually pulled him off the field before his 34th birthday.

Another item in Dempsey's favor is his postseason performance, especially his 1983 World Series MVP-winning job. Dempsey came up huge in that series, hitting .385/.467/.923. All of his five hits went for extra bases—four were doubles, and one was a home run. They say that flags fly forever; it can also be said that trophies never rust. That series was the highlight of his playing career, but it should be noted that Dempsey played at a high level in October in general, hitting .303/.370/.515 in 25 postseason games (he also saw action with the 1979 O's and the 1988 Dodgers). Hoiles, like Dempsey, led two Oriole teams into the postseason, but wasn't able to break through on the big stage, hitting .150/.306/.300 in 15 postseason games. His teams reached the ALCS both times, but never got to the World Series.

As if all that weren't enough, Dempsey earns bonus points for coming back to the Orioles as a coach in 2002. He remains a favorite among fans who remember not only his achievements as a player, but also the crowd-pleasing shtick that he served up to pass the time during rain delays.

The third-best catcher in modern Orioles history was one of the team's first, Gus Triandos. Triandos came to the team from the Yankees in November 1954 as part of a voluminous swap of seventeen players. He played mostly first base in 1955 as Hal Smith handled the bulk of the catching, but by 1956 Triandos was the Orioles' primary catcher, and from 1957 to 1959 he was an All-Star.

Though ordinary behind the plate (like many, he struggled to catch Hoyt Wilhelm's knuckleball), Triandos was a powerful hitter, compiling a .249/.326/.424 line as an Oriole. In 1958 he tied Yogi Berra's AL record for home runs in a season by a catcher with 30, a mark that stood until 1982. Somehow, he hit just ten doubles that year, and just seven doubles (against 25 homers) in 1959. In fact, he hit more homers (142) than doubles (119) during his Orioles tenure, and ditto in his career (167 to 147). An obvious inference is that he had some of the slowest feet around, and his career totals of six triples and one stolen base (in one attempt) confirm that. Catchers like him were the basis for the phrase "runs like a catcher."

Although his bat petered out in 1962, Triandos gave the Orioles several good years behind the plate, and he deserves to be remembered among the Oriole all-time greats. His 107 Win Shares and 37 WARP-3 place him a step behind Dempsey and Hoiles among the Orioles' best catchers.

Best of the rest

Honorable mention is awarded to Andy Etchebarren (1962, 1965-1975), Ellie Hendricks (1968-1972, 1973-1976, 1978-1979), and Mickey Tettleton (1988-1990). Etchebarren and Hendricks formed an effective catching tandem for the Orioles during the team's first stretch of greatness from the late '60s to the mid-'70s. Etchebarren hit from the right side, and Hendricks from the left, so they formed a natural offensive platoon; neither was a great hitter, but they were both effective receivers who combined to catch many excellent pitching staffs.

Etchebarren caught the '66 champions and finished with more Win Shares and WARP-3 than Hendricks, who arrived in 1968. But Hendricks gets a boost from his twenty-six years of service as the club's bullpen coach after the end of his playing career. He also performed better in the postseason, hitting .273/.355/.424, far superior to Etchebarren's October averages of .154/.225/.215.

Tettleton may seem an unlikely candidate to make the list because of the brevity of his Oriole career. He spent just three seasons in Baltimore, and roughly one-fourth of his games as a Bird were as a designated hitter. But this is where "peak" enters the picture. Though he was so-so behind the plate and did not hit for high average, Tettleton was the epitome of power and patience. He hit .245/.363/.438 as an Oriole with highs of 26 home runs in 1989 and 106 walks in 1990. His excellent 1989 season (.258/.369/.509) was a major reason for Baltimore's improbable "Why Not?" resurgence and may have helped spur regional sales of Froot Loops, his favorite breakfast cereal. In his three seasons of work for the Orioles, Tettleton averaged more than five wins over a replacement player per year, a rate that compares well to the top three catchers on this chart. Had Tettleton stayed with the club three more years, he likely would have crept up near Triandos in the rankings. Fortunately, in 1990 the Orioles had a young Hoiles waiting in the wings, so they were able to let go of Tettleton without losing much at catcher.

Next up: first basemen.